As Europe faces a potential heating crisis this winter as war rages on and Russia holds its precious gas hostage from the desperate Europeans, an uncertain future faces the continent.

It was this that inspired me to look to the past to see how mankind has survived winters without gas for hundreds of thousands of years. We didn’t need Russia then, more specifically its gas, so why do we need it now?

It all comes down to energy, and throughout the ages, humans have used a variety of methods to heat their homes when winter wraps its icy claws around the land. We used to simply ensconce ourselves around a campfire and hope for the best, and eventually this became the hearths and fireplaces we still use today.

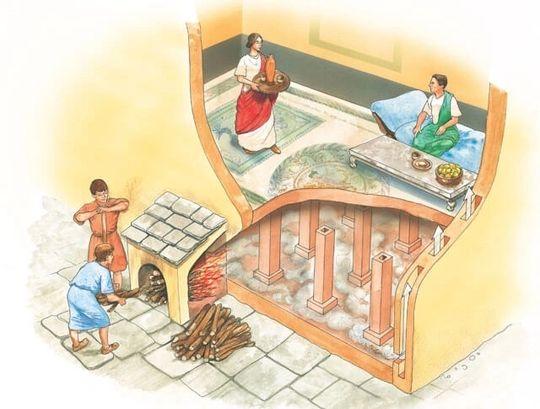

Ondol in Korea – circa 5000 BCE

Our journey begins just west of where the sun rises: Korea. Using direct heat transfer, an underground contraption called an ondol was used to heat the floors of ancient Korean homes. The heat came from woodsmoke

that then heated an adjacent stone floor created using masonry techniques of the day. It was underlain with wooden pillars creating hollow passages, or vents, for the hot air to pass through as it rose. An accessible hearth, called an agungi in Korean, would have been lit to provide the heat. An ancient source of power. At the end of the chamber would have stood a chimney to let the smoke out.

The most famous one was discovered in modern-day North Korea and has been dated to approximately 5000 BCE, and it pulled double duty as a central heating system and a stove for cooking.

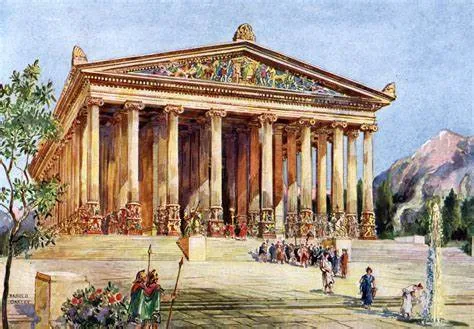

Ancient Greece – Temple of Artemis at Ephesus

The city of Ephesus has a longstanding history of matriarchal goddesses, and arguably that tradition culminated with the Temple of Artemis, often considered a wonder of the ancient world. This wonder was built with an interesting floor, one that was later used in perhaps the most ironically famous act of arson in history.

The floor of the temple was constructed with flues, which conducted hot air from braziers to directly heat the floor via convection, though please note that the last part of that statement is mostly extrapolation based on the information I could find as there wasn’t much about the design of the floor specifically that I could dig up. I felt the need to mention it solely die to its fame and the example of heating it gave.

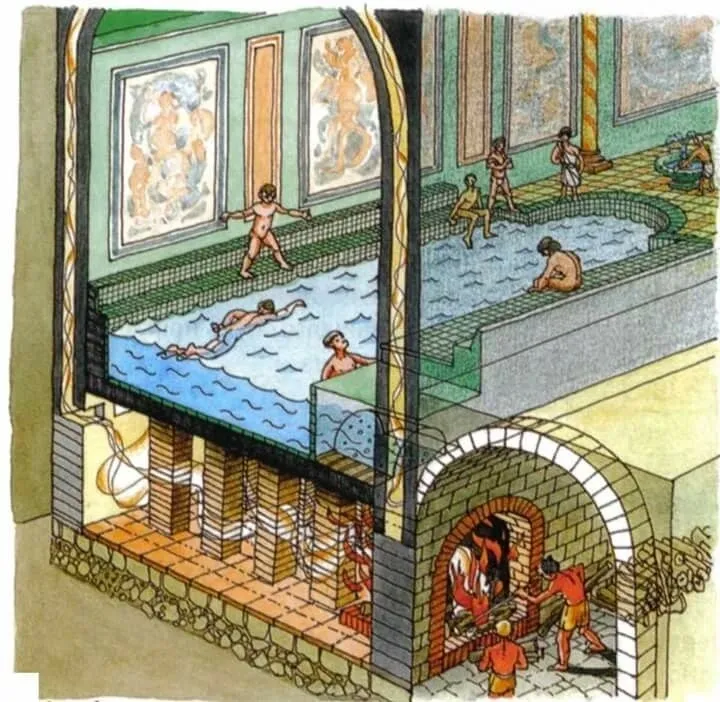

Ancient Rome– Hypocaust

In his De Architectura, Vitruvius describes the construction and functionality of the Roman hypocaust, which was written in about 15 BCE, a far cry from 5000.

Hypocausts were used all over the place in the Roman world, from private homes to large public works, and were commonly used in bath houses. Using a series of ventilation chambers beneath the floor, similar to the ondol but with a more complex network, the hypocaust allowed heat to travel from the furnace. The ceiling to the larger chamber was supported by pila to create a large underground “room'” that was then populated by these ventilation chambers.

In some places, inlaid systems of piping behind walls provided heat from the sides. Rooms were often organized based on how close to the furnace they would be, and therefore how much heat they needed for whatever purpose they served. For example, a kitchen would be closer than a bedroom.

The invention of the hypocaust is credited to a man named Sergius Orata in 95 BCE, who of all things, was a well known and widely regarded oyster breeder. He is the one credited with the use of heating for the baths and widely known for his love of luxury. Which is a narrative that fits nicely considering most of his wealth was derived from making comfortable things even more comfy.

Spain to Now

After the fall of Western Rome, the hypocaust fell into disuse alongside it, though it remained in the East, alongside other technologies like Greek Fire and eventually Damascus Steel.

People reverted back to simple fireplaces, campfires, and stoves for a long time before the Spaniards latched onto a few novel ideas that evolved from the memory of the hypocaust.

Hi, this is a comment.

To get started with moderating, editing, and deleting comments, please visit the Comments screen in the dashboard.

Commenter avatars come from Gravatar.