A Damascene Dagger

Let’s seek out the truth, then. Take a dive with me into a rabbit hole of metallurgy, history, and legend.

Stories abound of this mythic steel possessing the ability to slice straight through the barrel of a rifle as if it were paper, or finely cut a feather-falling hair unfortunate enough to find itself split upon the blade.

The truth, however, is a bit murkier than these finely spun tales.

Imagine for a moment the dusty markets of Damascus, then capital of Syria and one of the most prominent cities in the Levant, swords and blades with a watery sheen could be found uncovered as a merchant rolled back his tarp. In a voice hoarse from perhaps months on the road, he would have taken advantage of the stories spread by crusaders upon encountering these blades. They would have watched their inferior weapons splinter and break when assaulted by an apparent watery gleam with a sharp edge, the very gleam gazing at you now from the peeled tarp. Any good Muslim wishing to push back against the pale-faced horde from the European continent would want one of these. For the right price, of course.

The name “Damascus” steel is surprisingly contentious. The most obvious answer is to say that these weapons were manufactured and/or sold in the city of Damascus, hence the name.

A differing perspective follows the etymology of the word “damas” being the root word for “watered” in Arabic. This being because of that watery gleam I mentioned earlier, which mimicked the patterns of “Damask” fabrics also manufactured and sold in Damascus.

Though one could just call it splitting hairs.

The characteristics of the blades themselves included the trademark watery sheen, resistance to shattering, as they were possessed of the ability to keep a bend even when “flexed beyond their elastic limit”, and the capacity to retain a sharp edge for long periods of time. This could have meant less maintenance when it came to sharpening them, though they still required care like all other blades.

"An iron sword from an Iron Age megalithic burial at Thelunganur in Tamil Nadu, India."

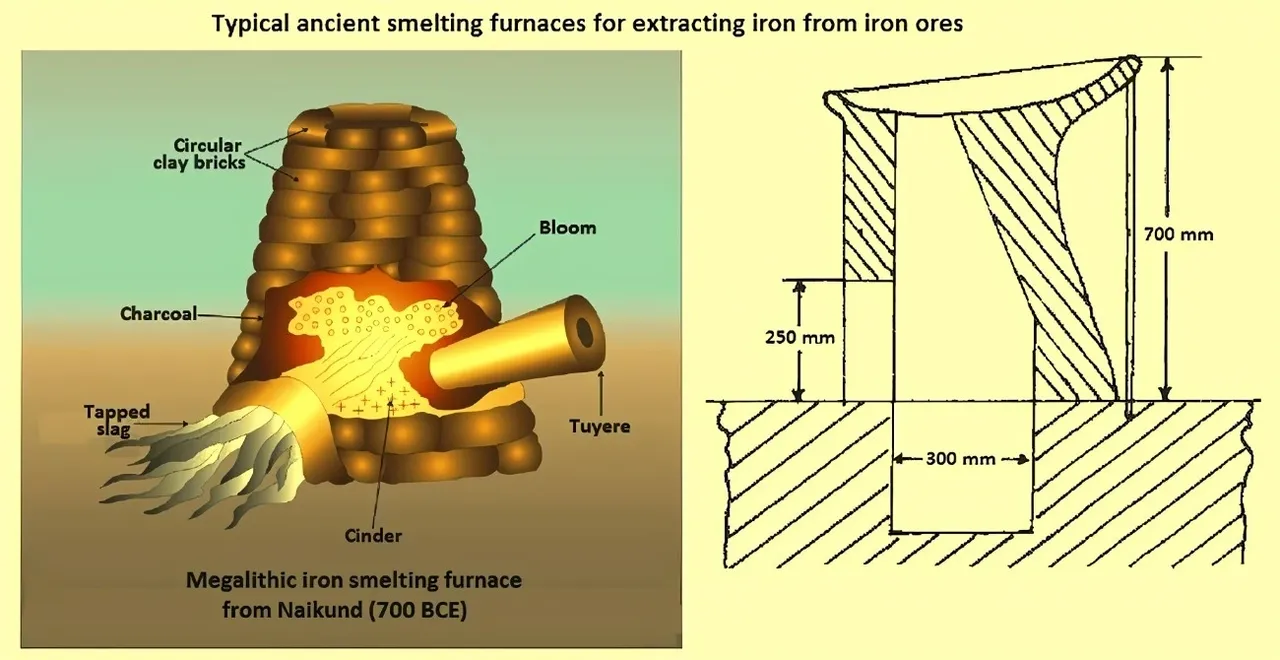

Megalithic Iron Smelting Furnace from Naikund (700 BCE)

Now, I could go on and on about the process to create these majestic blades, but I will include links in the photos themselves for further reading if you’re interested in where my information comes from.

Now we come to the “Lost” part…right?

Well, not exactly.

The secret to this is that Damascus steel was never actually “lost” in the classical sense. Techniques changed over time as access to the original materials became less and less obtainable for varying reasons, one of which could be the Mongol invasion that brought the Islamic Golden Age to a screeching halt even as the new Mongol Empire absorbed the Silk Road, thus separating Damascus from the Indian and Sri Lankan markets in which Seric steel had been pioneered. This marked a sharp dip in Damascus steel development perhaps when it was needed most. Forget the pale-faced invaders, the Mongols made mincemeat of the embattled Islamic States, outclassing the crusaders.

Production then continued to slump, finally ceasing around 1900. Not all that long ago in the grand scheme of things. The final nail in that coffin being the British Raj.

If you look up Damascus steel online, you’ll find modern reproductions of the ancient metal all over Amazon, Ebay, and Shopify. Why is that? Was the technique never really lost, or did we rediscover it somehow?

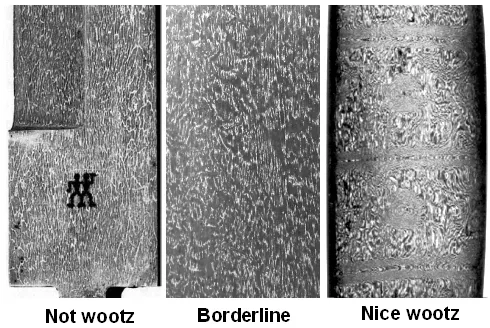

Differences Between Pattern-Welding & Wootz Steel

Go out and buy your damascene blades friends, for this technology has been more or less resurrected, and we can all enjoy it. Whether you’re cutting through infidels, Mongols, crusaders, or simply attacking a steak, they’re here to stay. That merchant on the dusty streets of Damascus would be grinning from ear to ear at that, so let him show you what he’s got.

For the right price, of course.

(Note: I inserted the paper written by Verhoeven and Pendray as a link from the Wootz Diagram above that describes the differences there. Just to avoid confusion. If you’re curious, I highly recommend reading their paper.)