Artist Depiction of Siphons Spraying Greek Fire Across a Battlefield

We do love to romanticize it, don’t we?

After Diocletian split the Empire among his Tetrarchs, an east and a west were established as a direct result of this bisection. The West fell while the East lived on. How?

Well, aside from paying its enemies to simply skip the Eastern provinces and head over to plunder the West, they also kept the spirit of Rome alive. Rome was a Kingdom, a Republic, then an Empire. Rome is dead, long live Rome. The civilization of Rome survived, as deceptive as that may sound. Through ingenuity and invention combined with that crazy ability to adapt, the East was still standing, and as the embers of the West were snuffed out, the East lit a torch.

Greek Fire is believed to have been invented by an architect and chemist named Kallinikos, from Heliopolis, Syria. This is according to historian and Orthodox Saint, Theophanes the Confessor. He writes:

Theophanes the Confessor

-St. Theophanes the Confessor

The torch has been lit. Let’s see how they used it.

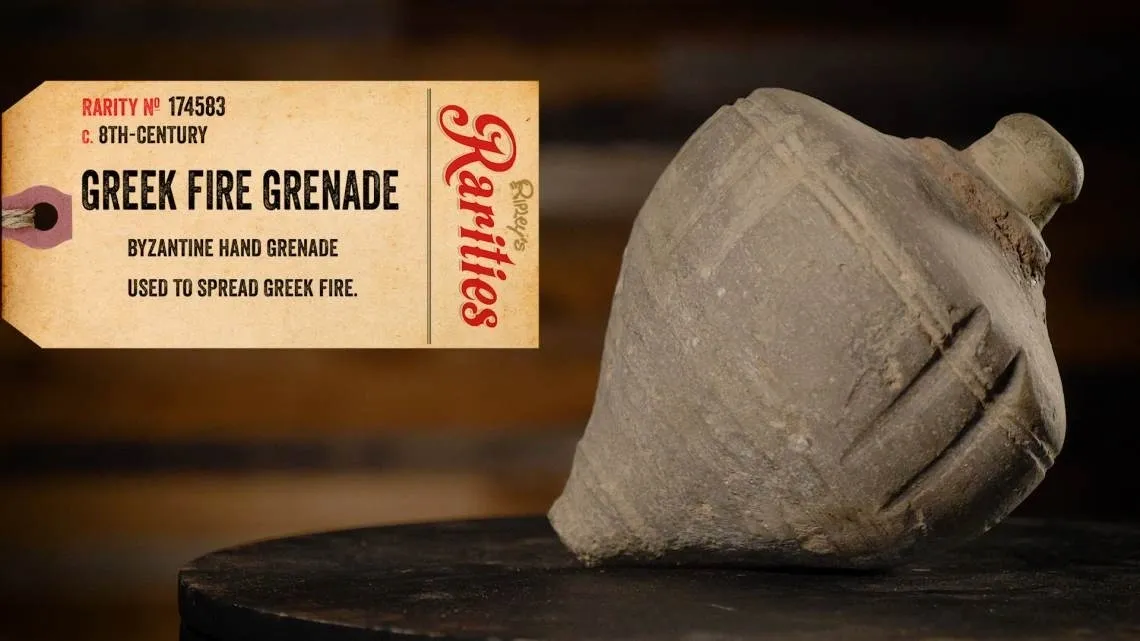

8th Century Greek Fire Grenade

As a result of this astonishing effectiveness, the composition of Greek Fire, also known to me as Medieval Napalm, was a closely guarded military secret. Shortly after Kallinikos’ arrival, engineers and chemists would have been frantically testing this new technology in a myriad of ways, one of which included the use of medieval grenades, which had been developed in Persia by the Sassanids. The difference would have been the velocity and duration of the explosion as well as the heat of the flames themselves, intensifying the experience for any unfortunate enough to find themselves in the paths of one of these incendiary devices. These grenades would have been hand thrown and made of typical pottery.

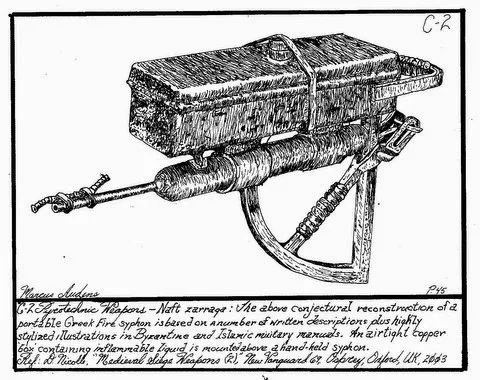

Conjectural Drawing of a Reconstruction of a Portable Greek Fire Siphon

Greek Fire Used in Naval Combat Against Viking Longships by Joseph Feely

Naphtha is a mixture of crude oils and assorted “fossil fuels” like coal. Quicklime appears as a white powder derived from the refinement of limestone and/or seashells. Sulphur would have also been known more colloquially as Brimstone, and it is a naturally occurring substance known for its wretched odor and flammability. Other likely candidates are wax, resin, and saltpeter.

Regardless, the sheer devastation of these devices, their implementation in the Eastern Roman Navy, and the tales of battle that abounded by the survivors at the other end of the nozzle all served to instigate a mythos that served them well. It became a deterrence for many years, and imitation devices would propagate as the centuries wore on.

Of course, all good things must come to an end. Eastern Rome, whether due to loss of resources, trade routes, or collective dementia regarding the recipe, eventually lost of one of its greatest weapons. During a council, it was decided that Greek Fire was simply too violent to continue using on the battlefield, despite protestations from those in the military.

This torch, too, eventually flickered and waned, only leaving a puff of smoke in its once devastating wake. Unlike Damascus Steel, Greek Fire has yet to be rediscovered, if ever. Besides, even if it was, I doubt the Geneva Conventions would allow for its use in a militaristic capacity. After researching the topic, I can’t say I’d blame them. O

This torch, too, eventually flickered and waned, only leaving a puff of smoke in its once devastating wake. Unlike Damascus Steel, Greek Fire has yet to be rediscovered, if ever. Besides, even if it was, I doubt the Geneva Conventions would allow for its use in a militaristic capacity. After researching the topic, I again can’t say I’d blame them.

(Note: I was unable to find a proper diagram of the siphons used on warships, so I went with the portable one instead to give you an idea. The depiction below is a little treat for Assassin’s Creed fans with minimal relevance. 🙂